By S. TANABE, A. ZANDVAKILI, A. KOHN; Neurosci., Albert Einstein Col. of Med., Bronx, NY

This group tackled a long-standing question in the field of decision-making: how do you tell the degree to which a single neuron “weighs in” on a behavioral choice? The question is important, but hard to get at via traditional single cell recording methods, especially for a fine discrimination task as the authors used here.

To get around this problem, this group recorded from 15-30 neurons in V4 while well-trained subjects made decisions about the orientation of a stimulus. As predicted, they didn’t find a strong relationship between the firing rates of single neurons and the subjects’ choices, but things changed dramatically when they looked at the population level and used a linear classifier. What might account for this? The authors argue that in high dimensional state spaces, the decision axis and variability axis are aligned. This means that even if a given neuron is a key player in a decision, the relationship between its firing and the animal’s choice might be weak.

At the end of the talk, the authors suggested a “trick” for evaluating the degree to which decision and variability axes are aligned: they shuffled the trials and found that sometimes the classifier did better! The effect of trial shuffling on the classifier, they argue, offers insight into the weighting profile of the neurons. I haven’t heard of anyone taking this approach before- it will be interesting to test on other datasets, especially those on coarse discrimination tasks where the prediction differs.

churchlandlab.org selected as an official blog for 2013 SFN meeting

October 25, 2013

I am pleased to announce that my blog was selected as one of the official blogs for the Society for Neuroscience Meeting this year. I will focus on two themes: “Sensory systems and behavior” and “Cognition and Behavior”. You can also follow me on Twitter at @anne_churchland.

This is exciting news as there will be a wealth of fantastic  science to talk about at the meeting. But in the meantime, I’ve been arguing with students at Penn about the importance of an orthogonal representation of task parameters in the parietal cortex. They are a tough crowd and had many great questions after my talk today. In this photo, we are discussing the science at the edge of a pretty pond behind the biology building. Marino Pagan from Nicole Rust’s lab had some interesting ideas about new classification analyses we should try inspired by analyses they undertook in their recent paper.

science to talk about at the meeting. But in the meantime, I’ve been arguing with students at Penn about the importance of an orthogonal representation of task parameters in the parietal cortex. They are a tough crowd and had many great questions after my talk today. In this photo, we are discussing the science at the edge of a pretty pond behind the biology building. Marino Pagan from Nicole Rust’s lab had some interesting ideas about new classification analyses we should try inspired by analyses they undertook in their recent paper.

New ideas for making sense of big data

October 18, 2013

Okay, so suppose you’ve just measured responses in hundreds of neurons, over time, during a complex behavioral task. Now what?? My lab members and I attended a conference at Columbia this week focussed on this issue. The conference, organized by Mark Churchland, Larry Abbott, John Cunningham and Liam Paninski was sponsored by Sandy Grossman and is a timely topic: advances in recording and imaging technology have made large neural datasets the norm and understanding how to analyze such datasets is nontrivial.

The talks included one from our lab, in which I described our recent ideas about the posterior parietal cortex and its response during a high dimensional decision task. Our work dovetailed with several others at the meeting: For example, Chris Machens spoke about his demixing principal components analysis, an analysis we have been using in our data. Chris, along with his student Wieland Brendel,  developed this analysis to ask whether parameters that are mixed at the level of single neurons might be orthogonal at the level of the population. Observing an orthogonal representation in the population is important because it suggests that task parameters are represented in a way that could be trivially decoded by a downstream area.

developed this analysis to ask whether parameters that are mixed at the level of single neurons might be orthogonal at the level of the population. Observing an orthogonal representation in the population is important because it suggests that task parameters are represented in a way that could be trivially decoded by a downstream area.

In another talk, Jonathan Pillow described recent work from his lab on Bayesian nonparametric models for spike patterns in large datasets. The basic idea in “Bayesian nonparametrics” is to define models whose complexity grows gracefully with the amount of data available. Jonathan described an approach for modeling binary spike patterns using a Dirichlet process, which marries the parsimony of a simple parametric model (e.g., each neuron fires independently with probability “p”) and a “histogram” model that describes arbitrarily complex distributions over binary spike patterns. These models, which Jonathan’s group calls “universal binary models”, strike a happy medium between overly complex models and those that are so simple they fail to capture key features of spike data.

In another talk, Jonathan Pillow described recent work from his lab on Bayesian nonparametric models for spike patterns in large datasets. The basic idea in “Bayesian nonparametrics” is to define models whose complexity grows gracefully with the amount of data available. Jonathan described an approach for modeling binary spike patterns using a Dirichlet process, which marries the parsimony of a simple parametric model (e.g., each neuron fires independently with probability “p”) and a “histogram” model that describes arbitrarily complex distributions over binary spike patterns. These models, which Jonathan’s group calls “universal binary models”, strike a happy medium between overly complex models and those that are so simple they fail to capture key features of spike data.

Champalimaud scientists propose that complex movements offer insight into brain function

October 7, 2013

Last week I attended the Champalimaud Neuroscience in Lisbon, Portugal. I heard many fantastic talks, including those from Susana Lima, Dora Angelaki, Michale Fee and Matteo Carandini. I also got updates from many investigators with labs at the Champalimaud, a number of whom are thinking deeply about body movements: how to track them and what they tell us about underlying neural processes. I spoke with Megan Carey and some of her team who are investigating how sensory inputs are processed differently in the brains of moving versus stationary animals.

I also spoke in detail with Joe Paton whose lab has been tackling questions about how future decisions affect current movements. This approach builds on an existing body of work suggesting that a signature of developing decisions is sometimes evident in premotor areas, and even in the movements themselves. The animal’s in Joe’s lab are freely moving so getting handle on their complex full-body movements is a challenge. The standard approach is to track one or two parameters that might turn out to be important- head angle, for instance. Thiago Gouvêa along with Asma Motiwala, graduate students in Joe’s Lab, came up with an approach that is fundamentally different: rather than trying to guess what the right body parameter might be, they image the whole animal and then reduce the

I also spoke in detail with Joe Paton whose lab has been tackling questions about how future decisions affect current movements. This approach builds on an existing body of work suggesting that a signature of developing decisions is sometimes evident in premotor areas, and even in the movements themselves. The animal’s in Joe’s lab are freely moving so getting handle on their complex full-body movements is a challenge. The standard approach is to track one or two parameters that might turn out to be important- head angle, for instance. Thiago Gouvêa along with Asma Motiwala, graduate students in Joe’s Lab, came up with an approach that is fundamentally different: rather than trying to guess what the right body parameter might be, they image the whole animal and then reduce the

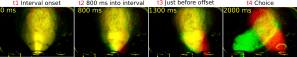

dimensionality of the large collection of images that results (see below, and also this video).

Imaged body positions where the rat will ultimately go left (red) and will ultimately go right (green) are overlaid.

This analysis will inform them which dimensions are the right ones. Because the approach doesn’t commit the investigator to a particular movement parameter, it allows for the fact that animals might be different from each other, or that a single animal might change over time: for instance, early in training showing anticipatory movements that are suppressed when the animal is an expert at the task. This is a new project, but has the potential to lead to a novel method of evaluating movements during decisions. Down the line, the movements could be related to neurons in different parts of the brain, and could help to interpret how those neurons contribute to a developing choice.

Cell death during development: who and why?

August 22, 2013

Cold Spring Harbor’s historic undergraduate research program continued this summer as 25 students from around the world joined us for 10 weeks. As co-directors of this program, Mike Schatz and I have the pleasure of seeing these students tackle challenging scientific problems and report their findings to their peers. Like last year, we were surprised both by the progress that the students made on their projects, and also by the way their scientific thinking changes over the course of the summer.

One project that particularly interested me this year was undertaken by Gregory Fuller, a student from Johns Hopkins who worked in the laboratory of Dr. Z. Josh Huang. Josh is one of the world’s experts on inhibitory neurons, and he has a particular interest in a class of such neurons called Chandelier Cells, named for their beautiful morphology. Like many neurons, numerous Chandelier Cells die over the course of development, mostly by a programmed cell death known as apoptosis. But Chandelier Cells are unique in that they tend to die later in development than most inhibitory neurons. Greg wondered, why do Chandelier Cells die so much later than other cells? And what will happen if their programmed cell death is delayed- will that have consequences for the circuit? Greg’s project took advantage of techniques that make it possible to block cell death: specifically, he studied brains from knockout mice that lack the proteins required for apoptosis. He closely examined tissue from different parts of the cortex, with a focus on layers 2 and 6 where the Chandelier Cells proliferate. One surprising observation was that perturbing the programmed cell death in Chandelier Cells not only caused them to proliferate, but also caused the appearance of some small cells that didn’t look much like Chandelier cells at all. Greg’s project is still at an early stage, but his observations are intriguing. Might the small cells be Chandelier cells that didn’t develop properly? Or are they a different class of neuron that was only made apparent through Greg’s manipulation? More work is necessary to get to the bottom, but the implications could be profound. Chandelier Cells likely play a key role in shaping cortical activity, and understanding how they are integrated into circuits during development may provide major insights into how they accomplish this.New insights from the CSH Imaging Course

August 2, 2013

Each summer, expert microscopists from around the globe descend on Cold Spring Harbor to teach an imaging course. The course consists of both lectures and labs. For the latter, the directors, lecturers and TAs rapidly assemble an unbelieveable assortment of microscopes. Within a week of arriving, they construct setups for imaging population activity, visualizing dendritic spines and uncaging glutamate. It’s incredible. My postdoc, Matt Kaufman and I have been sitting in on some lectures. We’ve heard about cutting edge work from Linda Wilbrecht, Valentina Emiliani, David Kleinfeld, Florin Albeanu and Jack Waters. Jack gave a great lecture about quantifying calcium sensors which Matt and I both enjoyed. Jack described an impressive bag of tricks for dealing with issues like background signal and cell-to-cell variability in brightness.

Each summer, expert microscopists from around the globe descend on Cold Spring Harbor to teach an imaging course. The course consists of both lectures and labs. For the latter, the directors, lecturers and TAs rapidly assemble an unbelieveable assortment of microscopes. Within a week of arriving, they construct setups for imaging population activity, visualizing dendritic spines and uncaging glutamate. It’s incredible. My postdoc, Matt Kaufman and I have been sitting in on some lectures. We’ve heard about cutting edge work from Linda Wilbrecht, Valentina Emiliani, David Kleinfeld, Florin Albeanu and Jack Waters. Jack gave a great lecture about quantifying calcium sensors which Matt and I both enjoyed. Jack described an impressive bag of tricks for dealing with issues like background signal and cell-to-cell variability in brightness.

We were also very fortunate in getting to pitch in as skilled TA Annalisa Scimemi assembled a 2 photon microscope. Annalisa is from the NIH but is en route to SUNY Albany to start her own lab. She explained to us how to align the laser correctly and direct it at a pair of mirror galvonometers to scan a piece of tissue. When the setup was up and running and we saw our first cells (at midnight, of course, see image at the top), we all cheered.

We were also very fortunate in getting to pitch in as skilled TA Annalisa Scimemi assembled a 2 photon microscope. Annalisa is from the NIH but is en route to SUNY Albany to start her own lab. She explained to us how to align the laser correctly and direct it at a pair of mirror galvonometers to scan a piece of tissue. When the setup was up and running and we saw our first cells (at midnight, of course, see image at the top), we all cheered.

Noise in decision-making: theory meets experiments

May 30, 2013

This week, my lab members and I attended a mini symposium at our own Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Organized by colleagues Tony Zador and Adam Kepecs, the focus of the day was understanding how the cortex and striatum interact to guide behavior. The speakers were Rui Costa, Linda Wilbrecht, Bernardo Sabatini, Anatol Kreitzer, and Tony Zador.

Linda Wilbrecht presented data aiming to understand the “currency” that the brain uses to make decisions. The talk included data from her recent Nature Neuroscience paper about behavioral effects of stimulating each of two classes of striatal dopamine neurons (D1-expressing and D2-expressing neurons). The first finding is that the two classes exerted opposite effects: stimulating D1 neurons caused more choices in one direction, while stimulating D2 neurons caused more choices in the opposite direction. The really interesting part, though, is that she found the effect of stimulation interacted with the animals’ reward history: for example, when stimulating neurons that caused more leftwards choices, she found the effect was enhanced if the animals had just experienced a few failed trials on the left side. WIthout stimulation, they would rarely go left after so many failures. But with the stimulation, they overcame this reluctance, and went left anyway. Understanding how recent reward history and current sensory information interact might one day give us insight into why the cycle of addiction is so hard to break.

Bernardo Sabatini described his experiments that aim to understand role of the direct versus indirect pathways. He stimulates each pathway optogenetically and looks at the effects on both behavior and firing rates of neurons in the motor cortex. He finds that the two pathways are not equal in the degree to which they affect firing rates and behavior. To visualize firing rates of motor cortex neurons, which are notoriously dynamic and complex, he reduced the dimensionality of the data using PCA. This analysis makes it possible to tell whether stimulation simply modifies an ongoing trajectory in high-dimensional space, or whether the stimulation drives the network to a novel state. The ability to perturb motor cortex and watch the resulting neural activity affords insight not just into striatal projections, but into developing motor commands as well.

Age-related cognitive decline: a transposon storm?

April 15, 2013

With the growing elderly population in the United States and around the world, questions about age-related cognitive decline are on everyone’s mind. Despite massive research into possible causes for age-related decline, numerous mysteries remain. A recent article in Nature Neuroscience, led by researcher Josh Dubnau at Cold Spring Harbor, suggests a new mechanism that may drive cognitive decline.

Josh’s lab uses Drosophila melanogaster (above) as a model system because of the feasibility of genetic manipulation in that species. The focus of their current paper is transposable elements: DNA sequences that can change where they are in the genome, potentially creating mutations or changing the size of the genome altogether. Readers who are not genetic experts might still remember Barbara McClintock’s famous corn that exposed the existence of transposable elements.

This new study identified transposable elements in drosophila that were active during normal aging. That might have been just a coincidence, except they found that a mutant with extra transposon expression had even more age-dependent cognitive decline. It was as if the mutants lost their cognitive sharpness more quickly than their wild type siblings. The mechanism by which this abnormal transposon activation affects cognition remains a mystery and the lab has yet to show that the abnormal transposons cause the cognitive decline. Nevertheless, this research suggests a new avenue through which we might understand, and ultimately prevent, the cognitive decline that so often accompanies aging. Perhaps the work might also provide insight into the variability in this process: might adults who suffer more rapid cognitive decline have more abnormal transposon activity? If so, what might be the cause of this? Answering such questions could cause a dramatic improvement in the lives of a large population.

Perceptions are fuzzy? Go with your prior.

April 5, 2013

Last week I was fortunate in having the opportunity to give some talks at the Riken Brain Institute outside Tokyo, Japan. I learned about fantastic ongoing work including during my visit: Tomomi Shimogori describe insights her lab has made about the driving force behind topographic organization, Hokto Kazama explained how his lab will use imaging to decode information in the fly brain about incoming olfactory signals and Keiji Tanaka described how the brain changes as learners transition from amateur to expert status

I also spent a lot of time with Justin Gardner discussing recent insights from his lab about perceptual processing humans. Recently, they have been delving into the neural basis of an established behavioral phenomenon: when subjects estimate the speed of low contrast gratings, they tend to mis-judge them a bit, rating them to be slower than they truly are. This has been interpreted by Eero Simoncelli’s lab as evidence for a “slow speed prior”: the idea is that we interpret sensory information by combining sensory evidence with prior beliefs. When the contrast is low, our perception is fuzzy, so we tend to go with the prior, rather than the sensory evidence. The Gardner lab is in a strong position to understand how this works for two reasons: first, they regularly image the brains of well-trained humans using fMRI; second, they have developed methods for decoding the signals they record, allowing them to understand how the brain changes with changes in the stimulus, such as contrast and speed. Using this approach, they find a clear signature of the slow speed prior, most noteably in the same early visual areas that represent the sensory evidence for speed such as V1 and MT. My lab is likewise interested in how priors are combined with sensory information. In the picture, you can see Justin and me arguing about whether insights from speed estimation priors apply to multisensory integration priors.