This past week, some lab members and I attended the Cosyne meeting in Salt Lake City. We heard emerging work about cue combination of spatiotemporal frequencies from Alan Stocker’s lab as well as a new perspective on LIP neurons from the labs of Alex Huk and Jonathan Pillow.

On the last day, we heard a fascinating talk by Deborah Gordon, an ecologist from Stanford, who studies ants. Dr Gordon has uncovered the signals that ants use when they make decisions about whether to go and forage for food. This decision is critical: if ants forage when conditions are poor, they dehydrate themselves and end up with little to show for their efforts. But by paying close attention to olfactory cues from co-foragers as they return, ants can make an informed choice about whether to look for food. The above image shows trajectories of ants in the lab: each line shows the path of a single ant as she wanders around, encounters colony-mates and adjusts her path accordingly. By automating the process of ant tracking, Dr. Gordon can simultaneously monitor the position of many animals and make broad conclusions about what they do.

Dr. Gordon drew an interesting parallel between ant behavior and neural transmission. She likened the pool of at-the-ready foraging ants to the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles that sit at the synapse. Just as the neuron integrates calcium over time, the ants integrate olfactory signals from other ants. And just as the neuron will spike when enough calcium is accumulated, the ant colony will “spike” out ants when enough signal from returning foragers is accumulated.

Many of us are familiar with seeing similar evolutionary strategies played out in different species, but this is something more. Here, it seems that there is a similar mechanism operating at very different levels: the level of the whole ant colony and the level of an individual, tiny synapse within one organ within one individual animal.

2012 Wrap-up

December 17, 2012

This post is to highlight the accomplishments of the students and postdocs in my lab in the past 12 months. We’ve made a ton of progress thanks to their hard work, talent and dedication. David Raposo (back row, right) published his first paper about rat and human behavior and made major inroads in understanding the neural circuits driving the behavior. John Sheppard (back row, left) has a paper in submission about cue weighting, and was awarded two graduate fellowships based on his proposed thesis work. Amanda Brown (front row, second from left) became an expert in animal training and is known around the lab as the “mouse whisperer” for her ability to generate stable, consistent behavior from these animals. Matt Kaufman (front row, left) joined the lab and has already got us thinking about the dimensionality of neural responses during decision formation versus during movement. Onyekachi Odemene (front row, second from right) joined on as our newest Watson School student and is already training mice effectively and laying the groundwork for a new direction in the lab. Mike Ryan (back row, center) joined us as a part-time technician on his way to graduate school and is already so good at making drives that we are plotting to keep him here. All told, it is a great pleasure working with these folks and I am excited to see what discoveries they will make in 2013.

Neuroscience on a large scale: optical imaging at Baylor

December 12, 2012

I visited Baylor college of medicine in Houston last week. I heard about ongoing work in a number of labs, including Dora Angelaki and David Dickman. I also met with Andreas Tolias whose work aims to understand how responses in primary visual cortex lead to perception. We discussed his new optical imaging approach of steering the two-photon excitation using AODs (acousto optic deflectors). With AOD, he can rapidly image the responses of large numbers of cortical neurons. He and his students this method to examine population activity and correlations of neurons in primary visual cortex. Previous attempts to examine these issues relied on much smaller populations of neurons, so Andrea’s approach has the potential to shed new light on age old questions about population coding.

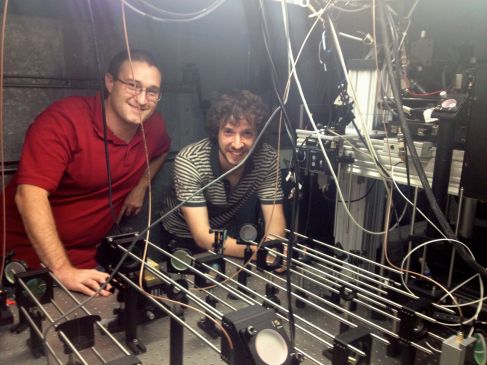

The picture below shows two of Andreas’s students, James Cotton (left) and George Denfield (right).

Two approaches for understanding schizophrenia gene DISC1 are reported at the Cold Spring Harbor in-house symposium

November 21, 2012

This week my lab attended the annual Cold Spring Harbor in-house symposium. We weren’t presenting this year, but heard about work from many labs here on campus. Some particularly interesting work focused on schizophrenia. Our interest in this topic stems from the fact that schizophrenics are known to have some abnormalities in how they use sensory information to guide behavior.

A major challenge in understanding the genetic basis of mental illness is that for may diseases, multiple genes are clearly involved. In the case of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for example, the genetic basis is clear, but studies of large populations show that two patients who suffer from the same disorder may have very different underlying mutations. The discovery back in 1990 of a large Scottish family with a high instance of schizophrenia and shared disruption of a gene called DISC1 affords a rare opportunity to understand the connection between genes and disease. But much remains unknown! At the symposium this year, two labs took very different approaches to tackle this problem.

Dick McCombie talked about his lab’s use of a genetic approach to further understand the mechanism by which mutations in DISC1 lead to bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. They seek to identify which proteins interact with DISC1 in the hopes of better understanding how its disruption might lead to disease. This could be important in understanding why some family members are susceptible to the mental disorders while others are not: perhaps there are also mutations in the proteins with which DISC1 interacts in patients, leading to a greater mutational burden that results in disease.

Bo Li‘s lab presented a poster that took a different approach to understanding how DISC1 mutations lead to disease. The poster was presented by Watson School student Kristen Delevich who probed the effect on neural circuits of DISC1 mutations. She measured electrophysiological responses in the medial prefrontal cortex and compared their magnitude and frequency in wild type mice and those with DISC1 mutations. Further, she took advantage of technology developed by Josh Huang’s lab that allowed her to disrupt DISC1 only in specified classes of interneurons. The attached image demonstrates the technique: she used a DISC1 hairpin and restricted it to the desired class of neurons. This targeted approach could reveal whether DISC1 mutations preferentially disrupt inhibitory neurons, an appealing idea since a disruption in the balance of excitation and inhibition has been speculated to have devastating consequences for cognition.

Taken together, these two studies begin to close the gap between basic science and the clinic: Using genetic tools that reveal candidate sites of disruption alongside electrophysiological tools that probe mechanism is a powerful approach. Given the devastating nature of schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and their frequency in the population, bridging this gap between the lab and the clinic is critical.

This past summer, I have been the co-director of the Undergraduate Research Program (URP) at Cold Spring Harbor. I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with 26 bright, enthusiastic students from the all over: we had students from Cambridge, Brown, Berkeley, the University of Barcelona, and many other places. Each student is placed in a lab and works on their own project for 10 weeks.

Although many students this year worked on innovative and exciting projects, I chose to highlight the work of Zach Collins, an undergraduate at George Washington University. Zach researched the expression patterns of inhibitory interneurons in collaboration with Partha Mitra’s lab and Josh Huang’s lab. Zach is particularly interested in whether the expression pattern of subtypes of inhibitory neurons is unusual in Autism. Although the possibility of disruption in the balance of excitation and inhibition has been previously suggested as an underlying cause for Autism, the precise differences in inhibitory circuits have not yet been thoroughly examined. Zach’s goal was to find an automated way to make 3-d reconstructions of mouse brains that show expression of sub classes of inhibitory neurons. By comparing the brains of a mouse model of autism with control mice, Zach and his colleagues will be able to identify where the differences in inhibitory neurons are most pronounced. The image below is a heat map of expression for Gad2, an enzyme marker of inhibitory GABAergic neurons. The section is from Pavel Osten’s lab; Zach worked to develop an automated algorithm to detect the labeled cells and quantify them across sections. Below that is am image of Zach (on the right) relaxing with fellow URPs Emily Glassberg and Ed Twomey (taken by Constance Brukin).

Parietal meet-up: a day of discussion about parietal connectivity and function across species

August 6, 2012

Last week we got together at Cold Spring Harbor with folks from NYU and MIT who share an interest in parietal cortex, but approach it from different points of view. Our lab, with a focus on neural circuits and decision-making, shared recent developments in rodent behavior and electrophysiology. Bijan Pesaran’s lab, from NYU, described their recent work exploring connections between sub-regions of parietal cortex in primate, and their emerging work on identifying neurons in the parietal cortex that project to frontal areas. Finally, Kathy Rockland, an anatomist from MIT, answered our many questions about injections, expression levels, and anatomical landmarks, and then later described her work connecting parietal cortex and subregions of the hippocampus.

At the moment, it is clear that may aspects of posterior parietal cortex are conserved from mouse to rat to monkey to human: in all species, the region gets inputs from similar thalamic nuclei (posterior nucleus in rodents and pulvinar + posterior nucleus in primates), and has feedforward connections to frontal areas and the superior colliculus. One thing that remains unclear is the degree to which species differ in the sub-regions that comprise posterior parietal cortex. In monkey, subdivisions are clear, although there is considerable overlap in the selectivity of neurons in each area. In rodent, the existence of subdivisions remains a mystery. Are they there waiting to be discovered? Or are the neurons in the most medial and lateral portions of the area functionally equivalent? We hope to be able to address these questions in the coming months.

The image below parietal cortex neurons in the rat (From Tomioka & Rockland) as well as a (somewhat incomplete) group photo taken from the cafe at Cold Spring Harbor Lab.

Last June, the Allen Institute for Brain Science released a map of mouse connectivity. They took a classic technique, injection of anterogradely transported viruses, and used it on a large scale. They made injections in multiple brain areas, scanned all the images with a 2-photon and put them on their website. This is an incredibly useful tool: all of the injections were done by the same group in the same way, making it feasible to compare the projections from one area with projections from another area. I am primarily interested in the posterior parietal cortex, so, with the help of my Cold Spring Harbor colleague Petr Znamenskiy, I did the following: I downloaded all the parietal injection images from the Allen Institute’s website, changed the color so that only the projections were visible, and then used tools on ImageJ to interpolate between slices and make the images into a 3-d movie. You can see it in this post: the white lines are projections coming from posterior parietal cortex and going to many regions of the brain.

Neuroscience in Crete

June 30, 2012

Manhattan Multisensory Meet-up

June 9, 2012

This week, my lab co-organized a multisensory journal club at NYU. Members from 5 labs at 3 institutions attended. In addition to our lab, we heard about the latest multisensory research from Denis Pelli’s lab, Mike Landy’s lab, David Poeppel’s lab and Maggie Shiffrar’s lab.

Two themes emerged in a number of the talks:the first was the role of timing in multisensory integration. James Thomas, from Maggie Shiffrar’s lab, presented psychophysical data describing judgments about biological motion using point-light walker simuli. He found that auditory stimuli,the sound of footsteps, helped subjects to distinguish real biological motion from scrambled biological motion. Interestingly, however, the auditory stimuli didn’t need to be precisely timed relative to the visual stimuli in order to see the effect. This is reminiscent of a recent paper from our lab: we find that subjects are better able to estimate stimulus rate when it is presented to the auditory and visual systems, but the exact timing of individual stimulus events doesn’t matter much. David Poeppel likewise reported a similar tolerance for temporal slop in the McGurk effect. We couldn’t agree on the explanation, however, and in the end, David and I made a bet about the degree to which the effect from the Shiffrar lab depended on the relative phase of the auditory visual stimulus (it was only for US$1, but I still await the results from James’ analysis with anticipation).

The second theme was highlighted by Mike Landy’s work: he has been studying how color and texture cues contribute to object segmentation. He reports that salient stimulus features bias subjects’ choices even when the subjects are explicitly instructed to ignore them. This is contrary to both my intuition and to scientific findings that feature-based attention can be modulated at will depending on the task at hand. Mike’s data suggests that, instead, feature-based attention may only operate in a restricted set of circumstances.

The lively discourse was lots of fun and the focus on behavior was especially compelling for my lab where our efforts are concentrated heavily on physiology at the moment. The picture above shows us at the end of the day.

How to keep a plan in mind: mouse neurons do it by sharing the job among members of a big population

May 25, 2012

Today in the Systems Neuroscience Journal Club at Cold Spring Harbor, my student John Sheppard presented a Nature paper by Chris Harvey, Philip Coen & David Tank entitled, “Choice-specific sequences in parietal cortex during a virtual-navigation decision task.” In the paper, the authors used optical imaging to monitor the responses of neurons in the posterior parietal cortex, an association area in the rodent brain that has many similarities to primate area LIP. As discussed in a posting on Action Potential, this article provided a different view of sustained activity compared to previous recordings in monkeys because the authors were able to measure the activity of many neurons at once. Further, they used a “virtual reality” setup to display visual images that updated as the animal moved. Although the animal wasn’t freely moving, he was able to navigate down a long maze by running on a ball.

One of the most intriguing findings from this paper is this: although the population as a whole remained active through much of the long delay period imposed on each trial, the activity of individual cells was only transiently elevated. This is quite different from area LIP in monkeys where, at least on a memory guided saccade task, the same neurons are active throughout a 1000 ms delay. Although this could be a species difference, I would put my money on the possibility that the difference is in the cells that were recorded. Optical imaging targets cells in more superficial layers, while the sharp electrodes used to record from primate LIP can be advanced to deeper layers. Further, because of the size of the electrodes, and the speed at which they are advanced, experiments with sharp electrodes may tend to be restricted to a narrower population of cells compared to those recorded with optical imaging, or even tetrodes. An intriguing possibility is that the transiently active cells from the imaging study might provide inputs that are temporally integrated and reflected in the output of thecells recorded in LIP.

In any event, the paper was great to read and provoked a lively discussion: see pictures below of Gonzalo Hugo arguing with John about error trials and Glenn Turner questioning whether errors versus corrects is really the key comparison.